Fishbone ingestion should be considered in cases involving an abdominal abscess with no clear cause, particularly in areas with fish-heavy diets, suggest the authors of a new study.

In a retrospective analysis published on 7 February in the European Journal of Radiology, authors led by Dr. Aya Ben Zitoun of the Department of Medical Imaging at Cayenne Hospital Center, French Guiana, examined 42 cases from Cayenne Hospital Center from May 2014 to 18 June 2023 involving abdominal complications caused by fishbone ingestion as determined by CT.

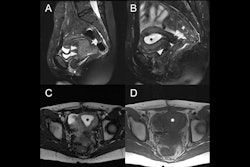

Various case examples of fishbone localization and related complications. (A) A fishbone (arrow) is visualized within the lumen of the rectum. The patient was asymptomatic, and no bowel wall thickening or adjacent fat stranding was observed, therefore this patient was excluded from analysis. (B) A fishbone (arrow) is impacted in the antral wall of the stomach, with no perforation but mild thickening of the antral wall (arrowhead). The patient presented with abdominal pain and inflammatory syndrome. (C) A fishbone (arrow) perforates the ileum, localised within an abdominal wall hernia (arrowheads). A fluid collection is forming at the site of perforation. (D) A fishbone (arrow) perforates the right colon, without pneumoperitoneum. Only epiploic fat stranding is seen (arrowhead). (E) A large epiploic fluid collection (star) is seen fistulizing into the abdominal wall (arrowhead). A fishbone (arrow) is visualized within the transverse colon. (F) The patient presented with a right liver lobe abscess (star) with hypodense infiltration (arrowhead) surrounding the collection and extending towards the hepatic hilum. A small linear foreign body, consistent with a fishbone (arrow), is seen within the liver.Ben Zitoun et al; EJR

Various case examples of fishbone localization and related complications. (A) A fishbone (arrow) is visualized within the lumen of the rectum. The patient was asymptomatic, and no bowel wall thickening or adjacent fat stranding was observed, therefore this patient was excluded from analysis. (B) A fishbone (arrow) is impacted in the antral wall of the stomach, with no perforation but mild thickening of the antral wall (arrowhead). The patient presented with abdominal pain and inflammatory syndrome. (C) A fishbone (arrow) perforates the ileum, localised within an abdominal wall hernia (arrowheads). A fluid collection is forming at the site of perforation. (D) A fishbone (arrow) perforates the right colon, without pneumoperitoneum. Only epiploic fat stranding is seen (arrowhead). (E) A large epiploic fluid collection (star) is seen fistulizing into the abdominal wall (arrowhead). A fishbone (arrow) is visualized within the transverse colon. (F) The patient presented with a right liver lobe abscess (star) with hypodense infiltration (arrowhead) surrounding the collection and extending towards the hepatic hilum. A small linear foreign body, consistent with a fishbone (arrow), is seen within the liver.Ben Zitoun et al; EJR

The researchers noted that fishbone ingestion is one of the most common causes of abdominal complications from involuntary foreign-body ingestion, especially in regions with a fish-heavy diet. They added that documented complications may include perforations, ulcerations, gastrointestinal bleeding, peritonitis, and intra-abdominal abscesses.

While the stomach is the most common site for perforation, the bones may migrate, resulting in complications outside the gastrointestinal tract, such as in the liver, biliary tract, or spleen. Although complications above the stomach may occur, these cases were excluded from the final cohort.

CT is the standard means of identifying fishbone ingestion, with the perforated region typically identified as a thickened intestinal segment or localized pneumoperitoneum with regional fatty infiltration. Abdominal radiographs are not as effective as CT, as the radiopacity of bones is dependent on the fish species, the researchers added.

Localizations of fishbones in the French Guiana study.Ben Zitoun et al; EJR

Localizations of fishbones in the French Guiana study.Ben Zitoun et al; EJR

Of the 42 cases involving abdominal complications due to fishbone ingestion as confirmed by CT, nearly all (41 of 42; 98%) had abdominal pain; in the 27 cases in which the presence or absence of fever was recorded, 56% (15 of 27) of the patients had fever.

CT showed that 41 of the 42 patients (98%) had bowel wall perforation (the sole patient without perforation had inflammatory bowel wall thickening). Only two of the 42 patients (5%) were found to have a pneumoperitoneum; there were no cases involving hemorrhage. There was intra-abdominal collection in 17 of the 42 patients (40%); of these patients, 12 had white blood cell values >10 G/L (values were missing for two patients in this group) and 15 of 16 patients (94%; one missing value) had a C-reactive protein (CRP) value >30 mg/L.

The authors wrote that in the only previous study focusing on abdominal complications due to fishbone ingestion (Goh et al), which had a cohort of seven cases, all patients were symptomatic, and 71% were found to have fluid collection; none had pneumoperitoneum. These findings are generally consistent with those of the present analysis, they added, with the caution that “the lack of pneumoperitoneum does not conclusively negate the possibility of bowel perforation by a foreign object,” as demonstrated by its presence in two cases in their analysis.

The most common locations for the fishbones emerged from the data: bones were located in the ileum in 11 of the 42 patients (26%), the liver in six (14%, with the note than five were in the left lobe of the liver); the bones were located in the stomach and the right colon for five patients (12%) for each. The remaining locations included the jejunum, omentum or peritoneum, appendix, anus, left colon, and sigmoid.

A 74-year-old man underwent a contrast-enhanced CT for colonic adenocarcinoma extension assessment (A). A fishbone was found, which was located purely into the omental bursa. There was no sign of gastric perforation (no pneumoperitoneum and no gastric abnormality) but there was discrete fat stranding around the fishbone with no collection (the patient was asymptomatic). Two and a half months later the patient presented with significant change in his general condition with an inflammatory syndrome alongside nausea. He presented to the emergency department and a contrast-enhanced CT was performed (B). In the portal venous phase, the fishbone had migrated into the left liver lobe forming an abscess of 5 cm (maximal diameter). The patient had a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 164 mg/l and a WBC of 14 G/L. The patient received antibiotic treatment and percutaneous drainage. On follow up imaging (C), 10 months later, the remaining fishbone was present but the liver abscess has completely disappeared.Ben Zitoun et al; EJR

A 74-year-old man underwent a contrast-enhanced CT for colonic adenocarcinoma extension assessment (A). A fishbone was found, which was located purely into the omental bursa. There was no sign of gastric perforation (no pneumoperitoneum and no gastric abnormality) but there was discrete fat stranding around the fishbone with no collection (the patient was asymptomatic). Two and a half months later the patient presented with significant change in his general condition with an inflammatory syndrome alongside nausea. He presented to the emergency department and a contrast-enhanced CT was performed (B). In the portal venous phase, the fishbone had migrated into the left liver lobe forming an abscess of 5 cm (maximal diameter). The patient had a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 164 mg/l and a WBC of 14 G/L. The patient received antibiotic treatment and percutaneous drainage. On follow up imaging (C), 10 months later, the remaining fishbone was present but the liver abscess has completely disappeared.Ben Zitoun et al; EJR

The most frequent approach for treatment in the analysis was open surgery (23 of 42 patients; 55%), followed by conservative treatment, including antibiotics (14 of 42 patients; 33%). Of the five patients not treated by these methods, four (10%) underwent endoscopic surgery to remove the fishbone; the remaining patient underwent percutaneous radiological drainage, in which the fishbone was left in place.

Of the 27 total patients who underwent surgery -- open or endoscopic -- the fishbone was successfully removed for 16 (12 of the open surgery patients; all 4 of those who underwent endoscopic surgery).

Ben Zitoun et al wrote that the fish species ingested were not specified in these cases, which could have provided further useful information. They also noted that fishbones may be underdetected as a cause for abdominal complications, as they may be confused with other foreign objects (e.g., medicine or other foods), and may be thin and small.

Furthermore, while the incidence of abdominal complications due to fishbone ingestion is low, the authors concluded that it should be considered in cases where the etiology of abdominal complications is unknown.

Read the full European Journal of Radiology article here.