Every few years, a campaign is launched to improve the diagnosis of a particular disease. There is often a catchphrase such as “Think x” or “Could it be y?” -- along with social media-ready hashtags and bright logos. Campaigns that spring to mind include aortic dissection, sepsis, and, oddly, porphyria.

Dr. Paul McCoubrie.

Dr. Paul McCoubrie.

The former two make sense, but raising awareness of a rare metabolic disease seems like an odd battle to choose. That was until I learnt that it has the same incidence as acute aortic dissection and can be similarly unpleasant. Every day is a school day, eh?

These exhortations from health groups, charities, and others are all done with the best of intentions. The conditions all share similar features: They are uncommon and easily missed, and they have considerable morbidity and mortality if untreated.

Such campaigns induce spikes in disease-related activity. For example, the rates of mammography screening in Australia doubled after Kylie Minogue was diagnosed with breast cancer. Porphyria? No Minogue effect yet, sadly. But there is considerable local variation. Some emergency departments (EDs) are aorta-mad: You merely sneeze in the waiting room, and they whip you in for a CT aortogram before you can wipe your nose.

It is a truism that any health campaign, new guideline, or “improved care pathway” always leads to more scans. No guideline says fewer scans. Moreover, scans should be done faster -- within two weeks, two days, or two hours. Radiologists see such medical news headlines, roll their eyes, and start joking about making the door to the ED hoop-shaped. Scan ‘em all as they walk in; it’d be quicker.

Incidence of disease in a scanned population is curiously quite variable, even allowing for fluctuations due to health campaigns. The major determinant is affluence. This isn’t a slight on the patients who I scan in the private sector; they have health anxieties like everyone else. It just so happens they usually have nothing seriously wrong with them. However, the NHS hospital that I work in serves a rather deprived area, and every second scan is abnormal.

Abnormal scan rate also depends on the referrers. Scans are more often abnormal if they are asked for by someone who is: (a) more experienced, (b) a generalist, and (c) a doctor. I make no apology for this. It might not be politically correct, but it is evidence-based. It is the major argument against allowing all and sundry to request scans. Sure, the patient gets scanned quicker. Which seems to be everything these days. It doesn’t matter if costs go through the roof and both quality and incidence go through the floor, so long as everything happens quickly.

The example of aortic dissection

Let us take, for example, aortic dissection. It's a nasty disease that kills unless treated urgently. Traditionally, aortic dissection was suspected if the patient had two of three features: a high-risk history, high-risk physical examination features, and high-risk predisposing conditions. Except it turns out that 36% of those with dissection only have one of three features. And 4% have none. So, it can be hard to diagnose.

So, the threshold for CT aortography is now so low as to barely exist, except that dissection is quite rare, somewhere around 1 per 1,000 patients pitching up to the ED. But given that roughly 70% of those presenting to ED do so because of pain, scanning for dissection can be like looking for a needle in a haystack.

When any patient could have an aortic dissection, few patients actually do. The incidence of positive CT aortograms can be as low as 1 in 200. Which leads to two predictable adverse outcomes.

First, health services absorb another strain on their resources. Certainly, the U.K.’s National Health Service (NHS) has no magic radiology tree from which we can pick fully qualified radiologists and radiographers. Nor do most health services have endless scanners and other facilities sitting idle. Hence, more scans for one condition mean worse waiting times for patients with other conditions.

Second, individual patients who have unnecessary scans suffer. Each unnecessary scan gives each patient a decent dose of radiation. Each unnecessary scan adds to their burden of discomfort and inconvenience. Each unnecessary scan induces a delay to their eventual diagnosis by adding a detour to radiology.

But it is the unpredicted outcomes that fascinate me. Below are the four main unintended consequences:

- Radiologist burnout. Although normal scans are quick to report, if over 99% are normal, then it feels all rather pointless. When the NHS can neither recruit nor retain radiologists, adding a feeling of ever-decreasing accomplishment doesn’t help.

- Surge in incidental findings. Incidental isn’t always trivial, but such findings need to be appropriately handled; otherwise, harm can result.

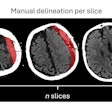

- Rise in false positives. Even a very good test that is 95% accurate will generate 5 false positives per 100 scans. Which, if your incidence is 1 in 200, means 10 false positive scans to every true negative. Hence, the beautifully accurate scans that you are used to are now peppered with uncertainty and dubious results.

- Rise in false negatives. A colleague from another hospital admitted to me that two of the last three aortic dissections were missed on the CT aortogram. They couldn’t easily explain why this was. They theorized it was bias from all the true negative and false positive scans, leading the radiologists to disbelieve their own eyes.

The upshot from this? When faced with a low-incidence but serious condition, it is vital that both clinicians and radiologists put their heads together. Health services cannot afford to scan patients where the chance of the condition is less than one in a hundred. Plus, it leads to a host of major predictable and unpredictable headaches.

The answer is surprisingly simple: Get experienced doctors to see and assess patients before scanning them. Fewer scans are asked for, scan positivity rate soars, costs drop, and everyone is happier. This approach is surprisingly simple, but it can be remarkably difficult. Plus, deploying more experienced doctors on the front line is not the current zeitgeist. So, the low-incidence problems are here to stay, I’m sorry to say. Just don’t say I didn’t tell you.

Editor’s Note: This article was first published on BJS Academy as a part of Paul McCoubrie's a "view from the dark side” series.

Dr. Paul McCoubrie is a consultant radiologist at Southmead Hospital in Bristol, U.K. Competing interests: None declared.

His latest book -- "More Rules of Radiology" -- is available via its publisher, Springer, as well as local bookstores ( ISBN-13 978-3031640933).

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of AuntMinnieEurope.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular vendor, analyst, industry consultant, or consulting group.