The human factors that contribute to errors in diagnostic radiology present stern challenges, but they can be mitigated with the right strategies, according to U.K. researchers.

“Just as there is a skill to imaging interpretation, there is a science to doing so safely," noted radiologists Dr. Jake Cowen and Dr. Rachel Oeppen and colleagues at the Portsmouth and Southampton Hospitals University NHS Trusts in an article posted on 17 June by the European Journal of Radiology. "Human factors in radiology are seldom discussed, and an awareness of individual limits and vulnerabilities is a useful starting point for radiologists to safely manage the increasing demand for imaging."

Practical changes to reduce interruptions and distractions, institutional efforts to minimize burnout, greater investment in the workforce, and an appreciation of cognitive bias can enable individuals, teams, and employers to reduce the risk of reporting errors, thus improving patient safety, they explained. Identifying and mitigating these factors is critical in reducing errors and improving accuracy in diagnostic radiology.

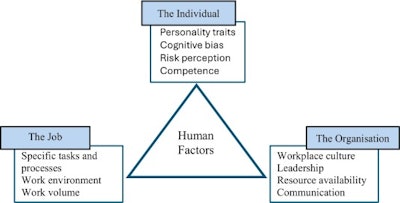

Triad of independent human factors.All figures courtesy of Dr. Jake Cowen, Dr. Rachel Oeppen, et al and EJR

Triad of independent human factors.All figures courtesy of Dr. Jake Cowen, Dr. Rachel Oeppen, et al and EJR

Noting the frequency at which radiologists are interrupted throughout their workdays, usually for short durations, the authors emphasized that the interruptions force radiology staff into a routine of task-switching that their review showed leads to cognitive fatigue and decreased efficiency, as well as an increased propensity for error.

The strategies they suggested for minimizing the effects of interruptions and distractions include modifying the layout of reporting rooms such that the reporting radiologist is relatively isolated from distractions and interruptions, such as clinician inquiries, which are handled by a duty radiologist/radiographer. They also recommend the use of electronic systems to prioritize: electronic vetting, instant alert systems for critical reports, and messaging systems for nonurgent requests.

Increased workload and time pressures, in turn, result in another human factor in reporting accuracy: fatigue and burnout. The authors pointed out that fatigue is a consistent factor in reporting errors, with studies showing significant increases in errors and discrepancies during night shifts, with longer shifts, and in the later hours of shifts.

The strategies suggested for combating fatigue include the highly pragmatic. For example, staff should take regular breaks and ensure adequate hydration during prolonged reading sessions. Other tactics are less tangible: “These results highlight the importance of recognition of individual limitations,” they wrote.

Unchecked fatigue and unmitigated workload stress may contribute to burnout. With burnout levels high in the field of radiology -- the authors cited percentages of 82% for overall burnout and 62% for high burnout levels -- and its known contribution to errors and reduction in work quality, finding effective strategies for combating it is imperative.

The researchers have suggested proven approaches to addressing burnout: ensure that staff feel supported and appreciated in their work, with appropriately balanced workloads that enable the employees’ autonomy and limit excessive reading duties; encourage personal measures such as regular exercise and consistent sleep patterns.

However, one of the newer approaches for addressing workforce shortages, the use of AI to assist with tasks, has the potential to be counterproductive in addressing burnout, the researchers stated. One cross-sectional study examined by the authors found that participating radiologists who frequently used AI in their tasks were at an increased risk of burnout. Nevertheless, they suggested, AI’s ability to assist in automating routine tasks, triage, and report production, as well as serve as a “cognitive safety net,” shows enormous potential to address some of the human factors involved with diagnostics, including burnout, provided the integration of AI is handled carefully.

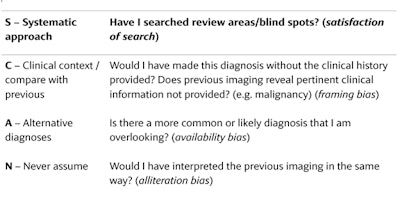

SCAN mnemonic for cognitive debiasing.

SCAN mnemonic for cognitive debiasing.

The authors addressed another significant factor contributing to human error in diagnostics: cognitive biases, which they summarize as “unconscious mental shortcuts that can lead to predictable errors.”

They noted that radiologists may often turn to a form of heuristic thinking (System 1 thinking) that involves intuitive pattern recognition developed over years of experience and training, which, while valuable, may introduce cognitive biases such as confirmation bias and anchoring if solely relied on. Rather, they wrote, radiologists must also incorporate what they refer to as System 2 thinking, a slower, more analytical mode of thought that is especially critical in more complex or ambiguous cases.

“Failure to switch effectively between System 1 and System 2 thinking can lead to cognitive error -- systematic deviations from rational judgement that can lead to diagnostic inaccuracies, as described,” they wrote.

Minimizing these sources of errors is less straightforward than for other factors; the authors suggest that observers learn to recognize the difference between the two systems of thinking (while acknowledging that System 1 can introduce cognitive errors) and be mindful of which is being employed. Additionally, they suggest the use of checklists as a method for reminding the reader of common biases.

The authors contend that the human factors that contribute to radiology errors and discrepancies are a topic not discussed frequently enough, but are important for ensuring staff and patient safety.

Read the full article here.