Examining the key factors that contribute to diagnostic errors in mammography and formulating strategies and structured procedures to combat them is critical to their prevention, an international team of authors wrote.

In an analysis published in Insights into Imaging on 5 January, Dr. Niketa Chotai, of the RadLink Women Imaging Center at Tan Tock Seng Hospital in Singapore, and colleagues examined the prevailing factors that lead to diagnostic error in mammography with the aim of recommending approaches to mitigate them.

A systemic, structured approach to combating the challenges leading to diagnostic mammography errors is required, they explained.

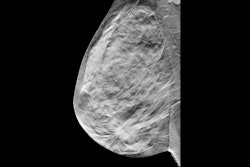

(a) Mediolateral oblique and craniocaudal screening mammograms in a 52-year-old woman demonstrated an isodense focal asymmetry in the lower inner right breast, projected over the retromammary fat (red arrows). This finding was not reported by the first reader, likely due to its location at the periphery of the image, and was reported by the second reader. Assessment with ultrasound (not shown) was unremarkable. (b) Breast MRI was subsequently performed, and the axial maximum intensity projection image revealed an irregular enhancing mass in the lower right breast, corresponding to the mammographic asymmetry (yellow arrows). Axial image obtained during MRI-guided biopsy, which revealed histopathology of grade 2 invasive lobular carcinoma.Chotai et al; Insights into Imaging

(a) Mediolateral oblique and craniocaudal screening mammograms in a 52-year-old woman demonstrated an isodense focal asymmetry in the lower inner right breast, projected over the retromammary fat (red arrows). This finding was not reported by the first reader, likely due to its location at the periphery of the image, and was reported by the second reader. Assessment with ultrasound (not shown) was unremarkable. (b) Breast MRI was subsequently performed, and the axial maximum intensity projection image revealed an irregular enhancing mass in the lower right breast, corresponding to the mammographic asymmetry (yellow arrows). Axial image obtained during MRI-guided biopsy, which revealed histopathology of grade 2 invasive lobular carcinoma.Chotai et al; Insights into Imaging

The authors identified the dominant factors contributing to faulty judgment and decision-making in reading mammograms: workload, time pressure, mental and emotional state, systemic obstacles (including communication breakdown and equipment issues), and the reader’s own cognitive biases.

Cognitive biases are particularly critical in making errors, they continued, noting that they involve the interplay of “erroneous judgment, misinterpretation, and ineffective heuristics.”

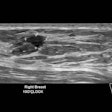

(a) Craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique screening mammograms in a 42-year-old woman reveal a small group of amorphous microcalcifications (red arrows) in the upper outer left breast. This finding was missed by one reader and recalled by the second reader. (b) Magnification imaging (dotted red arrows) demonstrates grouped fine pleomorphic microcalcifications. Stereotactic biopsy revealed intermediate-grade ductal carcinoma in situ.Chotai et al; Insights into Imaging

(a) Craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique screening mammograms in a 42-year-old woman reveal a small group of amorphous microcalcifications (red arrows) in the upper outer left breast. This finding was missed by one reader and recalled by the second reader. (b) Magnification imaging (dotted red arrows) demonstrates grouped fine pleomorphic microcalcifications. Stereotactic biopsy revealed intermediate-grade ductal carcinoma in situ.Chotai et al; Insights into Imaging

The common biases they observed included “satisfaction of search” (i.e., detecting an anomaly may prevent the radiologist from looking further for additional issues), anchoring bias (in which the reader remains set on a particular diagnosis even in the face of new and conflicting information), and confirmation bias (the reader selectively and unconsciously seeks evidence that buttresses a preexisting hypothesis rather than objectively considering all evidence).

Also of relevance were availability bias (disproportionate influence of recently-encountered cases and information), blind spot bias (the radiologist overlooks something subtle in an area not usually scrutinized), and inattention bias (in which abnormalities are missed due to distractions).

(a) Screening mammogram in a 44-year-old woman initially interpreted as normal by the radiologist on a particularly busy day. (b) Subsequent computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) analysis using Lunit INSIGHT MMG v1.1.7.1 annotated an isodense asymmetry with associated microcalcifications (red arrow) in the upper posterior right breast, seen on mediolateral oblique projection only. CAD flagged this area (red arrow) with a 38% likelihood of malignancy (red circle). (c) Retrospective review of a prior mammogram from a year ago revealed a small group of round microcalcifications in linear distribution (yellow arrow) in the area of CAD interest, not previously described. (d) Magnification imaging showed persistent asymmetry (dotted red arrow) with subtle architectural distortion and microcalcifications in the area of concern. (e) Ultrasound shows a corresponding irregular, nonparallel, hypoechoic mass with indistinct margins. Ultrasound-guided biopsy revealed grade 3 invasive ductal carcinoma.Chotai et al; Insights into Imaging

(a) Screening mammogram in a 44-year-old woman initially interpreted as normal by the radiologist on a particularly busy day. (b) Subsequent computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) analysis using Lunit INSIGHT MMG v1.1.7.1 annotated an isodense asymmetry with associated microcalcifications (red arrow) in the upper posterior right breast, seen on mediolateral oblique projection only. CAD flagged this area (red arrow) with a 38% likelihood of malignancy (red circle). (c) Retrospective review of a prior mammogram from a year ago revealed a small group of round microcalcifications in linear distribution (yellow arrow) in the area of CAD interest, not previously described. (d) Magnification imaging showed persistent asymmetry (dotted red arrow) with subtle architectural distortion and microcalcifications in the area of concern. (e) Ultrasound shows a corresponding irregular, nonparallel, hypoechoic mass with indistinct margins. Ultrasound-guided biopsy revealed grade 3 invasive ductal carcinoma.Chotai et al; Insights into Imaging

The researchers suggested different strategies for approaching and mitigating biases, such as a systematic, structured review and a checklist to challenge satisfaction of search, inattention, and blind spot biases, as well as increased awareness of possible alternative diagnoses to combat biases such as anchoring, confirmation, and availability. Additionally, they provided a list of regions that are common “blind spots” on mammograms, as well as suggestions for limiting contributors to the loss of focus that can result in inattention bias (e.g., regular training, breaks to avoid fatigue, and limiting environmental distractions).

Characteristics of lesions themselves constitute another factor that may affect the accuracy of interpretation. Intrinsic features of lesions, such as lesions that may appear only in one view, breast cancers that can mimic benign lesions, lesions that appear stable (but are not), and subtle architectural distortion, can all present obstacles in detection. The authors advocate more careful and systematic evaluation and second opinions, as well as greater use of digital breast tomosynthesis.

(a) A 45-year-old woman underwent a baseline screening mammogram, which was interpreted as normal by one reader. A second reader identified a possible isodense mass in the upper inner quadrant of the left breast, projected over the retromammary fat (red arrows, left craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique mammograms). (b) Spot compression left lateral-medial mammogram demonstrated an irregular mass with spiculated margins (red arrow) in the area of concern. (c) Targeted ultrasound demonstrated a correlating irregular hypoechoic mass with indistinct margins (yellow arrow). Ultrasound-guided core biopsy revealed invasive ductal carcinoma.Chotai et al, Insights into Imaging

(a) A 45-year-old woman underwent a baseline screening mammogram, which was interpreted as normal by one reader. A second reader identified a possible isodense mass in the upper inner quadrant of the left breast, projected over the retromammary fat (red arrows, left craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique mammograms). (b) Spot compression left lateral-medial mammogram demonstrated an irregular mass with spiculated margins (red arrow) in the area of concern. (c) Targeted ultrasound demonstrated a correlating irregular hypoechoic mass with indistinct margins (yellow arrow). Ultrasound-guided core biopsy revealed invasive ductal carcinoma.Chotai et al, Insights into Imaging

Along with idiosyncrasies in lesions, there are characteristics specific to patients that may influence the possibility of diagnostic errors, they added.

Breast tissue changes over time. Variations in morphology, including tissue density, patient use of hormone replacement therapy, and surgery, can all present challenges in detecting abnormalities. As a counter to these, “incorporating relevant background information is essential to aid interpretation and improve cancer detection,” according to the researchers. Adapting the positioning of the patient and the use of supplemental imaging using MRI or ultrasound are also recommended as potential mitigating choices to prevent errors.

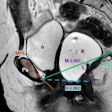

(a) A 49-year-old woman presented for an annual screening mammogram in 2019. Bilateral mediolateral oblique mammograms reveal dense fibroglandular tissue with possible architectural distortion in the upper right breast (red arrow). (b) Comparison with prior mammograms dating back to 2016 showed stability of this finding. (c-f) Further comparison with multiple prior mammograms dating back to 2011 revealed progressive, but subtle increased conspicuity (dotted red arrows) of the architectural distortion. (g) The patient was recalled for a targeted ultrasound that revealed an irregular, hypoechoic nonmass lesion (yellow arrows) with mixed posterior features. Ultrasound-guided biopsy revealed grade 1 invasive lobular carcinoma. The case highlights the insidious and slow-growing nature of invasive lobular carcinoma, which can mimic stability over short intervals and be challenging to detect on mammography, especially in dense breasts.Chotai et al; Insights into Imaging

(a) A 49-year-old woman presented for an annual screening mammogram in 2019. Bilateral mediolateral oblique mammograms reveal dense fibroglandular tissue with possible architectural distortion in the upper right breast (red arrow). (b) Comparison with prior mammograms dating back to 2016 showed stability of this finding. (c-f) Further comparison with multiple prior mammograms dating back to 2011 revealed progressive, but subtle increased conspicuity (dotted red arrows) of the architectural distortion. (g) The patient was recalled for a targeted ultrasound that revealed an irregular, hypoechoic nonmass lesion (yellow arrows) with mixed posterior features. Ultrasound-guided biopsy revealed grade 1 invasive lobular carcinoma. The case highlights the insidious and slow-growing nature of invasive lobular carcinoma, which can mimic stability over short intervals and be challenging to detect on mammography, especially in dense breasts.Chotai et al; Insights into Imaging

Finally, technical limitations may present obstacles in reading mammography. Improper positioning, inconsistent and suboptimal protocols, and poor equipment may lead to low-quality imaging. The authors’ suggestions included establishing and adhering to proper positioning criteria, ensuring settings are correct, and maintaining all equipment, with appropriate quality-control checks.

The changes needed to ensure high quality -- and minimize the potential for errors -- are systemic, according to Chotai and colleagues; establishing structured processes and procedures as well as quality assurance checks are key interventions that mitigate biases and ensure consistency. Likewise, structured training and peer feedback also aid in improving accuracy, along with the implementation of AI-based detection software.

“By learning from past mistakes and proactively addressing the common pitfalls highlighted in this review, radiologists can enhance diagnostic precision and contribute to more timely and accurate breast cancer detection -- ultimately improving outcomes for patients,” the authors concluded.

Read the article here.