Cinematic rendering has been drawing attention for its amazingly lifelike images of complex anatomy. But what will it take to move past the "wow" factor and integrate cinematic rendering into routine clinical use? Experts on the topic shared their insight in a British Institute of Radiology (BIR) podcast.

Following the publication of their pictorial review in the British Journal of Radiology, radiologists Dr. Steven Rowe, PhD, and Dr. Elliot Fishman from Johns Hopkins University discussed the current state of affairs regarding cinematic rendering, its potential contributions in the clinical setting, and the measures required for it to be incorporated into routine practice.

Cinematic-rendered images of a large abdominal aortic aneurysm. Courtesy of Dr. Steven Rowe, PhD.

Cinematic-rendered images of a large abdominal aortic aneurysm. Courtesy of Dr. Steven Rowe, PhD.Rowe is convinced that cinematic rendering will become one of the 3D techniques that are used almost universally in various applications of radiology practice. Fishman also thinks the technology has great potential.

"Depending on where you sit, you can come up with an infinite number of applications for cinematic rendering," Fishman said. "We're doing a lot of work now, but I have to admit we're basically scratching the surface of where things can go over the near term."

Added depth, intuition

Cinematic rendering is a form of 3D visualization of MRI or CT scans that, unlike volume rendering, involves a different reconstruction algorithm that simulates the propagation of light from a far greater number of directions, according to the researchers. Using this lighting model results in very realistic shadowing effects that show the relative anatomical positions of structures and gives a depth and intuition to how structures are related.

"The ability to create more lifelike images -- that's really the big advantage [of cinematic rendering]," Fishman said. "That bearing-lighting model is particularly critical the more complicated the structures are and the smaller the structures are, and it provides a much closer view to reality.... The more vascular-complicated the anatomy is, the better the technique works."

In recent years, Fishman and colleagues have used commercially available image-processing software (syngo.via VB20, Siemens Healthineers) to create cinematic-rendered images out of CT scans of various regions of the body, especially areas with considerable amounts of vasculature (BIR Publications, 9 February 2018).

"If a blood vessel is coursing out toward you [in a cinematic-rendered image], whether it's overlapping other blood vessels, you really do get a sense of that three dimensionally, almost as if you're holding a 3D-printed model in your hands," Rowe said. "I think this is a unique thing to cinematic rendering that really does help us in areas like chest cardiovasculature."

Beyond the cardiovascular system, the physicians have examined cinematic-rendered images of the musculoskeletal, renal (staging), small bowel, and oncologic (primary and metastatic tumors) systems. They have also evaluated craniofacial regions with deformities or trauma to the skull.

"If you named the body part, you could imagine where cinematic rendering is going to help you in terms of better diagnosis, better management, and in the end, most importantly, better patient outcomes," Fishman said.

Benefits clinician, patient

But how will the technology advance patient care? And who will benefit most from this technique?

In response to these questions, the radiologists on the podcast discussed the following various clinical applications of cinematic rendering:

- Surgery: One of the primary uses of cinematic rendering is to enhance the visualization of anatomy for preoperative planning, especially in rare and complex cases that often already involve some version of 3D imaging.

- Patient communication: "Patients are going to have a direct benefit from this in that, when they sit down with their surgeon and their counselor, the surgeons are going to show them these images, and I think the patients are going to be engaged by having access to these images," he said. "They're much easier to grasp than, say, our traditional volume-rendered images, which still have a kind of artificiality to them that make them more difficult to understand."

- Medical education: Using cinematic-rendered images can help medical students, residents, and clinicians learn anatomy and pathology in ways they have not before, according to Rowe. "They're going to be able to see, from imaging data, this lifelike, 3D representation of complex or difficult-to-understand areas of anatomy."

"Surgeons are going to want to see these [cinematic-rendered] images, almost demand to see these images, before embarking on complex procedures," Rowe said. "Surgeons are going to prefer these because of the depth of these images and the intuitive nature of how the images display the anatomy."

Whereas CT consists of thousands of slices, many of which clinicians need to file through, cinematic rendering is capable of representing these slices in just a few images. The Johns Hopkins group plans to continue investigating the potential benefits of using cinematic rendering and has yet to come across any cases for which the method produces images that are "not good."

Need to simplify, quantify

Currently, the technology needed to create cinematic-rendered images is only available at a few centers, due in large part to its high computing demands. Fishman and Rowe have already witnessed computers increase their processing speed such that images that formerly had to be downsized before being moved can now maintain their resolution. They foresee even faster speeds in the next couple of years -- improving image quality and allowing viewing to be more interactive.

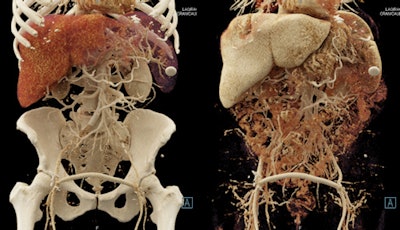

Cinematic rendering creates lifelike photorealistic images. Image courtesy of Dr. Elliot Fishman.

Cinematic rendering creates lifelike photorealistic images. Image courtesy of Dr. Elliot Fishman."The technology is almost advancing so fast that we're having trouble keeping up with figuring out what we can do with it," Rowe said. "The technique itself is so new that we probably haven't even come across or envisioned a lot of what will be the highest impact application of this method."

These advances, in turn, may make cinematic rendering easier to manage -- more "intuitive" -- for clinicians not necessarily accustomed to using it.

"Even something that's very good, if it's complicated, people will not use it. So it needs to be available, it needs to be intuitive, and it needs to be transparent to be able to use," Fishman said.

Furthermore, the investigators are exploring ways to quantify just how helpful integrating the technology into clinical practice is, how often it is helpful, and when it should be used. They suggested that quantifying the benefits of cinematic rendering would help move it toward reimbursement.

"If there's no reimbursement, the reality tends to be that physicians tend not to order the studies and the radiologists tend not to do the studies," Fishman said. "One of the things that will make this process real is to have some good data and really good science behind it."

For now, the team remains hopeful and excited about the future of cinematic rendering in medicine.

"What we've seen already is remarkable and what we've been able to do is remarkable," Rowe said. "We have only just begun to realize the potential."

To listen to the BIR podcast, click here.