Hundreds of promising target molecules have been identified in preclinical studies for possible use as novel cell imaging agents. But how many are ever likely to be used in real patients? And who will pay the costs of the clinical trials needed to prove their value?

The answers to these two burning questions are, respectively, "very few" and "nobody," according to speakers at a special panel discussion held in Leiden, the Netherlands, during last month's final workshop for participants in the European Commission's ENCITE (the European Network for Cell Imaging and Tracking Expertise) research program. An entirely new system for funding major multinational clinical research on diagnostic products will need to be created by industry, academics, and regulatory bodies, they maintained.

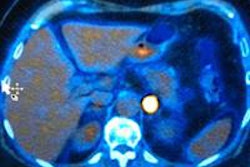

ENCITE was a 4.5-year project bringing together 28 international academic centers, coordinated by the European Institute for Biomedical Imaging Research in Vienna. Its goal was to promote the development of the novel biomarkers needed to increase the clinical effectiveness of MRI and other imaging modalities and to hasten the development of personalized medicine.

The collaboration has produced some important success stories, like that described by Kevin Brindle, PhD, from the Molecular Imaging (MRI and MRS) Laboratory, Cancer Research U.K. Cambridge Research Institute. Studies on biomarkers based on hyperpolarized C-13-labeled pyruvate and fumarate substrates have now entered clinical trials. The technique, based on the lower radiofrequency resonance of C-13 molecules, promises to increase the sensitivity of MRI examinations by 10,000 times and could be particularly useful in monitoring response to therapy in oncology patients, he said.

The first study in prostate cancer patients has already begun at the University of California, San Francisco, and three trials will begin next year in Cambridge for breast cancer, lymphoma, and glioma.

"The key question here is: will it do anything useful? We may not know for another 10 to 15 years as no amount of preclinical work will be able to tell you if a biomarker makes any difference to the therapeutic outcome. The only way to find out is [to] push ahead with the clinical trials," he said.

Many papers about promising nanomaterials don't go beyond the proof of principle stage, according to Dr. Fabian Kiessling.

Many papers about promising nanomaterials don't go beyond the proof of principle stage, according to Dr. Fabian Kiessling.

Looking at the prospects for molecular imaging over the next decade, speakers were anxious about the financial risks of translating promising preclinical results into useful diagnostic tools. Dr. Fabian Kiessling, chairman of experimental molecular imaging at RWTH-Aachen University in Germany, estimated the costs of recruitment for an initial clinical trial -- e.g. about MR cell tracking -- at several thousand euros per patient. It was impractical to suggest that the academic groups responsible for identifying the most promising candidate molecules will be able to afford to support the early stage translational research, but the pharmaceutical industry is unlikely to pick up the tab, he commented.

"Many papers have been published on promising nanomaterials but they don't go beyond the proof of principle stage. It is not enough to identify a receptor or to show that a molecule gets into the brain. Unless you can show what impact it has on the patient, then you won't persuade a company to develop a novel contrast agent as the medical insurance agencies won't reimburse the costs," Kiessling said.

Bertrand Loubaton, director of pharmaceutical and academic collaboration at GE Healthcare, Velizy Cedex, France, agreed that the limited financial returns mean traditional pharmaceutical industry is unlikely to be able to support this research.

"The problem when you stratify patients into niche markets is return on investment. We have so many fantastic tools sitting on a shelf because the economics mean it is impossible to develop them into a practical solution," he said, adding that around 500 potential biomarkers have been discovered with potential applications in the positron emission tomography field alone, but the vast majority are not patentable and the market would immediately open up to competitor companies. [Editor's Note: to read more about Loubaton's perspectives on molecular imaging, click here]

However, Mark Ellisman, PhD, director of the National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research in San Diego, California, insisted that industry's problems were of its own making.

"I cry little for Big Pharma, they have boxed themselves into this and the only way forward for them is to acquire good ideas from startup companies that have been supported by venture capital or government funding. Yet, these companies still have huge chemical libraries that are not being used. They haven't shown themselves capable of working in the best interests of the wider community," he said.

But perhaps the massive costs of developing conventional therapeutic drugs will work in the favor of companies developing diagnostic biomarkers for a narrow patient group, suggested Jeff Bulte, PhD, professor of radiology, biomedical engineering, and chemical and biomolecular engineering at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.

"If I am paying $100 to send a package across the Atlantic then I would be happy to pay an extra $5 to ensure that it is signed for and I have a guarantee that it has reached its destination. Some of the new therapeutic drugs cost $100,000 for a full course or treatment and that won't necessarily be covered by medical insurance. So if I was a patient I would be happy to pay more to ensure that the drug is reaching the target tissues," he said.

Loubaton argued that academic rather than industry research groups would continue to drive the development of the novel biomarkers that would allow personalized therapies. But there must also be greater collaboration between universities, companies, and regulators to devise new structures for validating the candidate molecules that is less complicated and costly than traditional methods, he said.

"At the moment, it is a nightmare. So we need to find a new model for developing new products that does not rely on old-fashioned phase I, II, and III clinical trials. Without that change, there will be no new biomarkers and without them, there is no personalized medicine," Loubaton noted.

To watch a video about how in vivo image-guided cell therapy is revolutionizing medicine and how ENCITE is making a strong contribution to this revolution, click here.