Modern imaging has replaced many of the older radiological techniques. These older examinations often involved considerable technical skills from both radiologists and radiographers, and they spent many years perfecting their skills.

It's easy to forget what medicine was like before ultrasound and cross-sectional imaging, and it's important for us to remember the older techniques and the pioneers who developed them. I can think of patients whom I looked after as a junior who might be alive today with modern imaging. This month's history column describes four of these techniques.

Translumbar aortography

Arteriography was developed in the 1920s with vascular injections from a cutdown. In 1923, Berberich and Hirsch introduced strontium bromide into the femoral artery of a living subject and obtained useful images. The idea was not unreasonable because many cadaveric injections had been made even before 1900. The main problems related to what could be injected and its toxicity.

In Portugal, Egas Moniz made carotid injections in 1927, initially with a cutdown and then by needle puncture. In 1927, building on the experience of Moniz, the team of Reynaldo Dos Santos, Augusto Lamas, and Pereira Caldas from Lisbon described direct abdominal aortic injections. Punctures were made into the aorta with a long needle in a variety of positions, including above the celiac trunk, above the kidneys, above the inferior mesenteric artery, and above the origin of the common iliac artery. The contrast used was a 100% solution of pure sodium iodide that was quite toxic. The injection was painful and therefore required anesthesia.

The translumbar aortogram became the standard vascular examination for decades and was routinely performed at Hammersmith Hospital in London when I started there as a radiology registrar in 1981, more than 50 years after the procedure was first described. There were surprisingly few complications from the procedure. The examination illustrated below was one I performed in 1982.

Translumbar aortograms like this one used to be the standard vascular exam. All images courtesy of Dr. Adrian Thomas.

Translumbar aortograms like this one used to be the standard vascular exam. All images courtesy of Dr. Adrian Thomas.Translumbar arteriography was replaced by catheter angiography from either the femoral or brachial/radial route. Now diagnostic angiography has been superseded by noninvasive imaging such as Doppler ultrasound and also CT and MR angiography. Angiography is now reserved for access for interventional procedures.

Bronchography

In bronchography, the bronchial tree was opacified with an opaque medium using a variety of techniques. In the illustration below, a catheter was used with contrast injected. The examination shows a normal right bronchogram. The examination was unpleasant for the patient, and there was therefore a high threshold of referral for performing the examination. The chest physician would be reluctant to submit the patient for the procedure unless there was a degree of confidence about the examination.

In bronchography, a catheter was used with contrast injected to examine the bronchial tree.

In bronchography, a catheter was used with contrast injected to examine the bronchial tree.The introduction of high-resolution CT (HRCT) has considerably changed attitudes about bronchiectasis. Because so many more patients are examined than were possible with bronchography, it is now known that bronchiectasis is much more common than physicians had previously appreciated. The first experimental bronchogram was performed by Karl Springer from Prague in 1906, which is surprisingly early. Over the years, the technique used many contrast agents, including colloidal silver and bismuth. In classical brochography, iodized oil was used, commonly introduced by tracheal injection. Contrast could also be introduced using a catheter, bronchoscope, or dripped over the back of the tongue.

Retroperitoneal air studies

In this technique, the retroperitoneum around the kidney is outlined by gas. Paul Rosenstein from Berlin and Humberto Carelli from Buenos Aires described the technique independently in 1921. A 10-cm needle was used to make a retroperitoneal injection. Rosenstein injected 600 mL of oxygen and Carelli about 200-400 mL of carbon dioxide. The examination was introduced in the days before the IVU to show the kidney. Rosenstein emphasized that it was "important that the radiologist became independent of the clinician for these pictures." He thought this technique was of value in the following:

Determining the presence of one or both kidneys. Removal of a solitary kidney would be a disaster.

Determining the size of a kidney.

Showing the presence of kidney stones more clearly.

Looking for displacements of kidneys. This would diagnose the "floating kidney" that was thought to be a cause of symptoms as a part of visceroptosis.

Diagnosis of renal tumors and tumors around the kidney.

Studying "acute stresses" of the kidney. In unexplained renal colic, the enlarged pelvis could be shown outlined by gas.

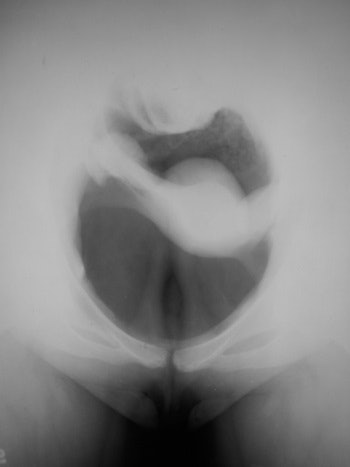

In later years, the technique was combined with tomography to show the adrenal gland. The examination illustrated below was performed in 1943.

This retroperitoneal air study was performed in 1943 using a 10-cm needle.

This retroperitoneal air study was performed in 1943 using a 10-cm needle.Diagnostic pneumoperitoneum/gynecography

In this technique, an abdominal radiograph is made following the induction of a pneumoperitoneum, and was developed by Eugen Weber from Kiev, Ukraine, in 1912. A specifically gynecological use was described by Otto Goetze from Halle, Germany, in 1918. The patient was placed head down and prone, and a pelvic radiograph was obtained with the pelvic viscera outlined with air. The uterus, bladder, and ovaries could be identified, and the bowel would fall out of the pelvis. Goetze said that he used the technique to diagnose pregnancy in the early months, infantilism, myomata, uterine and adnexal adhesions, pyosalpinx, and ovarian tumors. The patient illustrated below was examined in 1967 and the examination was normal. This was just before the introduction of ultrasound, which rendered the examination obsolete.

This technique, performed as late as 1967, was the predecessor to ultrasound.

This technique, performed as late as 1967, was the predecessor to ultrasound.To conclude, we are now so accustomed to modern imaging that we do not realize how difficult it was to make even what now are quite straightforward diagnoses a few decades ago. Peripheral vascular disease, bronchiectasis, renal disease, and pelvis masses can be elegantly demonstrated noninvasively. Our very success is what is putting pressure on our departments. Many more patients are now referred for HRCT to exclude bronchiectasis than were ever referred for bronchography. This has resulted in a paradigm shift. Traditionally, there was invasive diagnosis and invasive treatments. We now have noninvasive diagnosis and minimally invasive therapy. Indeed, the one implies and leads to the other. Minimally invasive therapy needs an accurate preintervention diagnosis so that the procedure can be planned and executed.

Dr. Adrian Thomas is chairman of the International Society for the History of Radiology and honorary librarian at the British Institute of Radiology.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of AuntMinnieEurope.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular vendor, analyst, industry consultant, or consulting group.