In a new article this week in Radiology, Dutch researchers fired up a 115-year-old x-ray machine, comparing its image quality and radiation dose with current technology. They found that the vintage system delivered a radiation dose that's 1,500 times the level of modern x-ray systems.

Despite the higher dose, the researchers said they were impressed that investigators in 1896 -- just a month after Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen's discovery of the x-ray -- were able to build an x-ray machine with parts found in the inventory of a local high school and acquire images that clearly demonstrated human anatomy. The lead author of the study was Martijn Kemerink, PhD, of Maastricht University Medical Center (Radiology, May 2011, Vol. 258:5).

Kemerink and colleagues said they were intrigued by the early research efforts in radiology that followed Röntgen's discovery. In particular, they were curious about the characteristics of these vintage machines, what it was like to work with them, and how much radiation dose they produced.

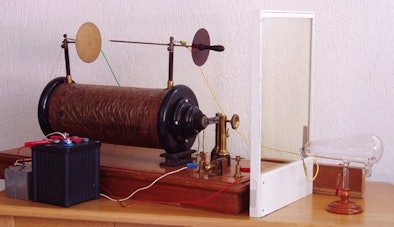

To answer these questions, they won permission to perform a series of experiments with an early x-ray machine developed by H.J. Hoffmans, a physicist and high school director in Maastricht, and L.Th. van Kleef, director of a local hospital. Hoffmans and van Kleef used the device to acquire a series of human images in 1896, but afterward the primitive unit became obsolete and was relegated to a warehouse in Maastricht.

It remained there until last year, when Maastricht University researchers received permission to repeat the early studies as part of a TV program on the history of healthcare in the region. They focused on a radiography study acquired on January 31, 1896, of van Kleef's 21-year-old daughter, repeating the exam with the machine but using a hand phantom instead. For comparison, they also imaged the phantom with a current radiography unit (BuckyDiagnost, Philips Healthcare), and measured radiation dose, image quality, and other parameters.

The researchers' description of the system sounds like something from a mad scientist's lab, and they characterize their experience as "little less than magical." The device's interruptor buzzed when in operation, lightning crackled within a spark gap, and a greenish light glowed from the system's tube as the smell of ozone wafted through the air.

|

| Early x-ray machine developed by Hoffmans and van Kleef. All images courtesy of the Radiological Society of North America. |

The machine was based on the use of Crookes tubes, glass cylinders that generate electrons when voltage is applied. One tube initially failed to function, but the researchers slowly increased the primary voltage to the point where the tube began to flash and produce x-rays. The researchers believe that a small part of the top of the anode pin had melted, interfering with the vacuum in the tube over the years.

Early radiographers might have been frustrated with the throughput of the vintage unit: The researchers found that they needed 90 minutes to acquire a hand image, compared with approximately 20 msec for the modern radiography system. What's more, Kemerink and colleagues characterized the x-rays produced by the system as "soft," due to a lack of filtration and other factors.

This led to a relatively high skin dose, which the researchers measured as 10 times that of the modern system when storage phosphor plates were used as receptors. However, due to the fact that inventors in 1896 were using photographic plates that required higher radiation doses, the researchers estimated that the dose delivered to the earliest radiography subjects was in the range of 74 mGy. That's as much as 1,500 times that of the 0.05 mGy registered with the modern system.

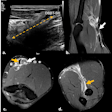

|

| Images of the hand specimen of an 86-year-old woman obtained with vintage x-ray machine (left) and a modern x-ray system (right). The exposure time with the 1896 system was 21 minutes. |

The researchers noted that the high radiation levels produced by early radiography systems often resulted in severe injuries to equipment operators. Health problems reported shortly after Röntgen's discovery included eye complaints, skin burns, and loss of hair. Many operators also experienced severe damage to their hands over time, which sometimes required amputation. Kemerink and colleagues reported that they recorded zero occupational radiation dose during their studies.

Although the study revealed the primitive nature of early work in radiology, the researchers said that ultimately they were impressed with the image quality of the device.

"Images of the hand specimen obtained with the antiquated system were severely blurred but were still awe inspiring, considering the simplicity of the system," they concluded.