It's time to brush up your knowledge of neonatal chest x-rays, and doing so will have a positive impact on patient management. That's the view of radiologists from Valencia, Spain, who presented their experiences at the 2015 annual meeting of the European Society of Thoracic Imaging (ESTI), held in Barcelona, Spain.

"It's important to know about the normal appearance and variability of the neonatal radiograph and the main findings in respiratory disease," noted Dr. David Uceda from the department of radiology at La Fe University Hospital in Valencia. "Furthermore, affirming the correct placement of catheters is critical to avoid complications."

Radiologists need to build their awareness of the normal neonatal chest x-ray and particularities that may mimic cardiopulmonary disease, remember the importance of the tubes and catheters used in pediatric intensive care units and their complications, and know about the main causes of neonatal respiratory distress and its findings on radiographs, he recommended.

The key phase of life

The neonatal period is a vital phase between birth and 28 days. It represents the time of greatest risk to the infant, and approximately 65% of all deaths that occur in the first year of life happen during this four-week period. In the first 24 hours of life, the main physiologic adjustments needed for extrauterine life occur, including the aeration of the lung and the transition to air-breathing.

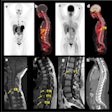

An inadequate pulmonary adaptation is the most important cause of morbidity in preterm neonates whose lungs usually are physiologically and morphologically immature, and they may develop respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), being surfactant deficient, and may necessitate prolonged mechanical ventilation, increasing the risk of lung injury with consequent bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD). All those abnormalities can be assessed by a chest x-ray.

Many newborns are monitored and treated in a pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) where the placement of tubes and catheters are monitored by chest-x ray.

During this critical period, it is essential to make a quality report, mentioning if the chest x-ray is optimal, the position of catheters, and signs of respiratory distress, keeping in mind that sometimes, normal varieties of the neonatal anatomy can mimic disease.

"Sometimes, the neonatal chest radiograph may strike fear into the heart of many radiology residents, especially if we are not used to working with newborn patients and we have no knowledge of their normal chest appearance," Uceda et al pointed out in their e-poster presentation at the ESTI annual meeting. "Furthermore, radiographs in the PICU are usually performed with portable x-rays and in a single view -- consequently, many of them are not technically optimal and it may be difficult [to form] a proper diagnosis."

Examination stages

The first step is to assess whether there is good inspiration or rotation because both can mimic pathology. A chest that is properly inspirated usually has a trapezoidal morphology, and the ribs are horizontally disposed and parallel to each other, with the cardiophrenic sinuses being well delineated. Some experts believe the anterior arch of the sixth rib is projected over the diaphragm. Any degree of rotation may simulate disease, such as cardiomegaly or a hyperdense hemithorax, and keep in mind that thymic configuration also may mimic disease and some signs are useful to identify its normal appearance, they advised.

Some tubes or catheters for treatment, nutrition, mechanical ventilation, and monitoring blood gases and blood pressure can be placed through an umbilical artery or vein, which serves as the access to endotracheal and nasogastric tubes. It is vital to ensure the correct positioning of these devices to avoid potential complications, according to Uceda and colleagues.

"There is disagreement about which is the correct position of the tip. Some authors suggest that the umbilical venous catheter should be placed next to the cavo-atrial junction, usually (but not always) at the level of ninth vertebral body (D9). An intracardiac placement may cause arrhythmias and even death in case of atrial wall perforation and cardiac tamponade," they noted.

For umbilical arterial catheters, the level preferred is the sixth vertebral body (D6) or L3-L5, but sometimes the tip may be placed between D5 and D9. It's important to avoid the origin of main arterial vessels, whose levels are:

- D12 (level of coeliac trunk)

- D12-L1 (level of the superior mesenteric artery)

- L1-L2 (level of renal arteries)

- L3 (inferior mesenteric artery)

- L4 (aorto-iliac bifurcation)

Some newborns with respiratory distress syndrome may require an endotracheal tube inserted via the mouth or nose into the trachea for mechanical ventilation, and it should be placed 1.5 cm above the carina (with the baby's head midline).

Catheter complications

Complications associated with catheters are usually related with an abnormal positioning, although sometimes they are inherent to the catheter. Catheters inside an artery or into the portal vein may cause thrombosis or portal cavernomatosis,

A chest x-ray usually shows bilateral and symmetrical ground glass opacities or a granulated pattern with diffuse distribution, and often the lungs are small. The radiographic findings are usually present shortly after birth, but they may appear after 12 to 24 hours.

Transient tachypnea of the newborn, also known as retained fetal fluid, is related to neonatal tachypnea for the first few hours of life, lasting up to one day. The tachypnea resolves by two days. This is more common in babies delivered by cesarean due to lack of thoracic compression, the researchers pointed out.

To view the full ESTI poster for free via the European Society of Radiology's (ESR) electronic poster system, EPOS, click here.