Heart failure is associated with gray-matter loss at MRI and a worsening of both memory and psychomotor skills. To a lesser extent, the presence of ischemic heart disease slows recall as well, according to a new study in the European Heart Journal.

Compared with a control group that included patients with and without cardiac ischemia, study participants with heart failure had lower scores on immediate memory, long-delay recall, and number coding. Those with ischemic heart disease (IHD) had lower long-delay recall, reported investigators from the University of Western Australia in Perth and several other institutions.

"People with heart failure lose gray matter in regions of the brain that are important for cognitive function. They also have worse immediate and long-term memory and psychomotor speed," lead investigator Dr. Osvaldo Almeida, PhD, wrote in an email to AuntMinnieEurope.com.

MRI exams correlated with the cardiac findings in the study, demonstrating a relative loss of cerebral gray matter in various cortical and subcortical regions of the brain in patients with heart failure.

A better understanding

"The question of whether [heart failure] is causally related to structural brain changes and cognitive decline is important because current approaches to the management of [heart failure] require the active participation of patients, who are expected to adhere to a complex treatment regime," wrote Almeida, Dr. Griselda Garrido, and colleagues. "The concern is that patients may have trouble complying with medical advice, which would lead to suboptimal management, more frequent health complications, and greater use of health services" (Eur Heart J, 31 January 2012).

Beyond these practical concerns, a better understanding of the association between heart failure and cognitive impairment could improve understanding of the mechanisms that link cardiovascular disease to cognitive decline in older patients, Almeida and colleagues wrote.

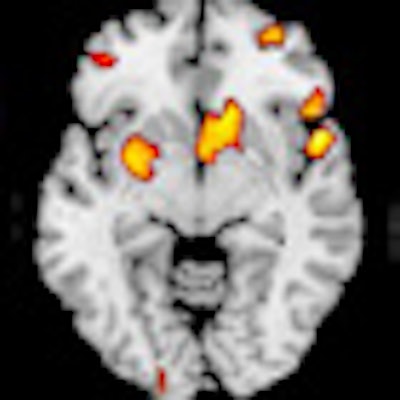

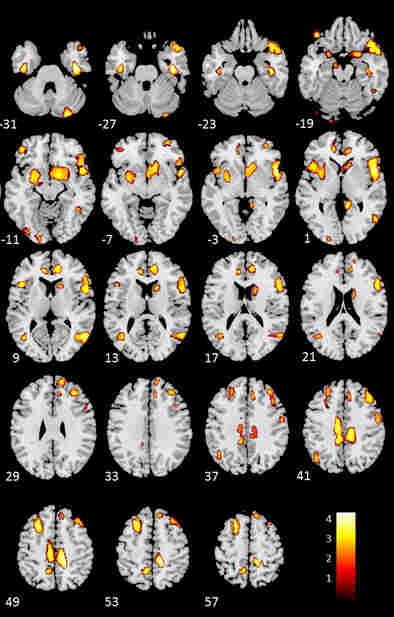

Areas of gray-matter deficiency are shown in yellow. Compared with healthy controls, participants with heart failure showed the greatest loss of gray matter in the left cingulate, the right inferior frontal gyrus, the left middle and superior frontal gyri, the right middle temporal lobe, the right and left anterior cingulate, the right middle frontal gyrus, the inferior and precentral frontal gyri, the right caudate, and the occipital-parietal regions involving the left precuneus. Image courtesy of Dr. Osvaldo Almeida, PhD.

Areas of gray-matter deficiency are shown in yellow. Compared with healthy controls, participants with heart failure showed the greatest loss of gray matter in the left cingulate, the right inferior frontal gyrus, the left middle and superior frontal gyri, the right middle temporal lobe, the right and left anterior cingulate, the right middle frontal gyrus, the inferior and precentral frontal gyri, the right caudate, and the occipital-parietal regions involving the left precuneus. Image courtesy of Dr. Osvaldo Almeida, PhD.The researchers were looking for evidence that adults with systolic heart failure showed evidence of cognitive impairment compared with normal adults, and whether the impairment correlated with a loss of gray matter at MRI.

The cross-sectional study included 35 participants older than 45 with heart failure (ejection fraction < 0.4), 56 with ischemic heart disease, and 64 controls without either condition. MRI was used to determine regional differences in cerebral gray-matter volume.

The study excluded people with a history of stroke or cardiac arrest, hearing or visual impairment, or evidence of clinically significant depressive or anxiety symptoms on the Mini-Mental State Examination.

Images were acquired on a 1.5-tesla system (Symphony, Siemens Healthcare) with a repetition time of 2830 msec, echo time of 4.48 msec, a matrix of 256 x 256 x 172 mm, and a voxel size of 0.9 mm3.

All images were evaluated by experienced neuroradiologists, who used the resulting reports to guide their search for artifacts. The images of 13 participants were excluded for poor image quality, leaving 155 patients for analysis.

The results showed that "participants with heart failure had lower scores than controls without ischemic heart disease on immediate memory, long delay recall, and digit coding, whereas those with [ischemic heart disease] had lower long delay recall scores than controls without ischemic heart disease," Almeida and colleagues reported.

Those with ischemic disease had a Cambridge Cognitive Examination of the Elderly (CAMCOG) and scored 1.8 lower (p = 0.101) than noncardiac controls. Those with heart failure scored 2.8 points (p = 0.029) lower than healthy controls. Adults with ischemic heart disease had lower long-delay recall scores than controls without ischemic heart disease (p = 0.047).

Gray-matter deficit

Compared with healthy controls, the brain regions of participants with heart failure showed the greatest loss of gray matter in the left cingulate, the right inferior frontal gyrus, the left middle and superior frontal gyri, the right middle temporal lobe, the right and left anterior cingulate, the right middle frontal gyrus, the inferior and precentral frontal gyri, the right caudate, and the occipital-parietal regions involving the left precuneus, the authors reported.

"The relative loss of gray matter among participants with [ischemic heart disease] compared with healthy controls was much less extensive, but affected overlapping regions," including the left medial frontal cortex, the left cingulate and precuneus, the left and right parahippocampal gyri, and the right and left middle temporal gyri.

"Contrary to expectations, our results showed no evidence of cognitive deficits in people with [heart failure compared with ischemic heart disease]," the authors wrote. "However, we found a relative loss of regional [gray matter] among participants with [heart failure] compared with [ischemic heart disease] that was less extensive but had a similar topographic distribution compared to healthy controls, suggesting that the changes may be relatively specific to heart failure."

The structural nature of MRI was useful in demonstrating that people with heart failure display more widespread and extensive brain changes than adults with ischemic heart disease, the authors added.

"Previous studies had already reported that people with [heart failure] have worse cognitive function than healthy controls, but it was unclear if those deficits were due to confounding," Almeida and colleagues wrote. "As far as we are aware, this is the first study that included an additional [ischemic heart disease] control group that shares common risk factors with [heart failure], which allowed us to show that the cognitive losses may be a nonspecific consequence of increasing cardiovascular disease burden."

The researchers found no brain regions in which controls with or without ischemic heart disease had more gray matter than heart failure participants.

The subtle deficits that were measured, barely lower than the controls and unlikely to be associated with overt clinical impairment, make it unlikely that they can be explained by reduced left-ventricular ejection fraction, comorbid conditions, or biochemical markers.

The results also suggest that male gender and older age increase loss of gray matter, the researchers wrote.

"Our study shows that people with [heart failure] experience loss of [gray matter] in brain regions that are relevant to cognitive function and that compromise performance on cognitive tasks that require mental effort," Osvaldo and colleagues concluded. "Importantly, our results are consistent with the observation that people with [heart failure] have trouble adhering to complex self-care advice, and suggest that simpler approaches to self-management may be required."

Additional research is needed to clarify the physiological pathways that link heart failure to the loss of cerebral gray matter and cognitive impairment, and longitudinal surveys could determine whether the observed changes are progressive, the authors concluded.

"We are currently finalizing the follow-up of a cohort of people with heart failure to find out if the changes that we observed are progressive in nature," Almeida stated.